Hydrogeology of Mozambique: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 230: | Line 230: | ||

|Named Aquifers||General Description||Water quantity issues||Water quality issues||Recharge | |Named Aquifers||General Description||Water quantity issues||Water quality issues||Recharge | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Unconsolidated aquifers cover a large part of the Mozambique basin, especially south of the Save River; and occur in river valleys and in some dune and coastal areas across the country. | ||

Key aquifers include sand layers within clayey alluvium; loamy silty to medium grained aeolian and beach/marine sands; and areas of weathered fine grained clayey sands overlying consolidated rocks. Less frequent, but highly productive, are thick sandy and gravelly alluvium in valleys. | |||

A belt of dune sands is developed along the entire coast of southern Mozambique, south of the Save River. These porous aeolian sands form a regional unconfined aquifer which can be very productive, as shown by boreholes in the Ponta de Ouro and Tofo aquifers, and can contain fresh groundwater. Permeability decreases from the coast inland, as a consequence of increased clay content. These unconsolidated sands are frequently underlain by more productive deeper consolidated aquifers, and there can be hydraulic continuity between the upper unconsolidated and deeper consolidated aquifer. For example, dune sands along the Inhambane coast overlie very productive limestones of the Jofane Formation, except in the area around Inharrime, where the dunes cover the low productive argillaceous sandstones of the Inharrime Formation. | |||

Significant thicknesses of alluvium have been developed along the main river valleys, and may form productive, stratified aquifers with good water quality. The aquifer layers can be confined or unconfined, depending on local circumstances. The central reaches of the Limpopo and Incomati have especially high-yielding prospects, with specific yields of up to 20 m³/h/m. | |||

|| | || | ||

||In most areas of the southern dune belt, the nearness of the aquifer to the sea, and sometimes to lagoonal inland depressions, means that the aquifer often contains brackish to saline water, which limits its use. However, there is fresh groundwater between Homoine and Massinga. | |||

In alluvial aquifers along the main river valleys, groundwater is generally of good quality. However, in the lower reaches of the main main valleys increased groundwater mineralization is often seen, as a consequence of occasional marine inundations or longer term sea-water intrusions near the river mouth. | |||

In the centre of the Incomati valley, the good prospects are offset by the existence of highly mineralized groundwater. | |||

|| | || | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 244: | Line 256: | ||

| | | | ||

|| | || | ||

|| | || | ||

|| | || | ||

| Line 258: | Line 269: | ||

|| | || | ||

|| | || | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 269: | Line 279: | ||

|| | || | ||

|| | || | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 276: | Line 285: | ||

|Named Aquifers||General Description||Water quantity issues||Water quality issues||Recharge | |Named Aquifers||General Description||Water quantity issues||Water quality issues||Recharge | ||

|- | |- | ||

| || | | | ||

|| | |||

|| | || | ||

|| | || | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Groundwater Status== | ==Groundwater Status== | ||

===Recharge=== | |||

Reliable information on natural aquifer recharge in Mozambique is very scarce. Only a few studies have been conducted, in a few small areas. Recharge to sandy soils around Maputo was studied by IWACO in 1985 and was found to be somewhere between 140 and 185 mm per year, which is around 20% of the total precipitation. In other areas with sandy soils and higher precipitation, recharge was found to be higher, for example, 210 and 350 mm per year, or around 30% of annual rainfall, near Pemba. In drier areas with less permeable soils, such as the semi-arid Chitima region near Tete, recharge values of less than 10 mm per year were estimated (IWACO 1985, DNA 1987). | |||

===Groundwater quantity=== | ===Groundwater quantity=== | ||

There are many potential problems linked to the use of groundwater in Mozambique. Little information exists on the present status of groundwater quantity, and there is no quantitative information on groundwater use and recharge. Before groundwater can be used on a large scale for irrigation or other uses, extensive research is needed (DNA 1987; British Geological Survey 2002). | |||

Groundwater has a significant role to play in the supply of drinking water, but is currently only used sparsely for irrigation due to the following factors: | |||

• Mozambique still has enough areas that can be developed for irrigation using surface water resources. | |||

• There is limited to no information on the potential of aquifers and yields of individual boreholes. | |||

• Large areas in southern Mozambique are deemed unsuitable for groundwater abstraction due to salinity issues. The exact extent of these areas is undetermined. | |||

It seems that the lack of information (which means there is an unknown risk of drilling low yielding boreholes and/or incurring high drilling costs) is a larger constraining factor than the actual potential of the groundwater. As well as this, there is a general consensus that surface water is more cost-effective for irrigation than groundwater. The potential for, in particular, large surface water irrigation schemes is still present in Mozambique, and thus the interest for groundwater is low. | |||

Furthermore, the following can be concluded: | |||

1) There is little knowledge of groundwater use around non-perennial rivers | |||

2) Groundwater for irrigation is mainly used for subsistence farming, except for certain labour intensive areas around Maputo. | |||

3) Legislation of groundwater abstraction is in its infancy in Mozambique. Capacity is very limited presently. Technical assistance and capacity training in this area is essential. | |||

4) Groundwater is probably underutilised at present, as potential users do not have knowledge of or access to the groundwater potential in their area. | |||

===Groundwater quality=== | ===Groundwater quality=== | ||

Little information is available on the quality of groundwater in the aquifers of Mozambique. The available information suggests that the groundwater is for the larger part fresh and of acceptable quality, though often of limited quantity, especially in the aquifers of the Basement Complex and the Volcanic Terrains. | |||

Significant salinity problems are experienced in some parts of the Tertiary aquifers in the south, as a result of natural seawater intrusion, forming areas with brackish groundwater. In large parts of Gaza, Maputo and Inhambane Province, groundwater in the main aquifer (from 20 – 80 m depth) has Electrical Conductivity values well above the WHO drinking water standards of 2000 µS/cm. These values also make the groundwater unsuitable for many crops and for livestock watering. In some particular instances (e.g. at Chokwe and Chibugo), extra deep boreholes (100-150 m) have been drilled to reach fresh water in aquifers. Such boreholes are, however, too expensive to consider for irrigation (particularly as proper sealing of the upper saline aquifer needs to be achieved). | |||

There is risk of pollution in the vicinity of industrial and urban developments, including from sewage effluent, from centres of petroleum and chemical manufacture, and from ports, as well as from agricultural activity. Pollution incidence is likely to be greatest in the coastal lowlands (DNA 1987, British Geological Survey 2002). | |||

Localized groundwater pollution is known to be occurring in the Chokwe (Gaza Province) area, where extensive irrigation has taken place (using surface water) since the 1930s. This has raised the local groundwater table and has led to increased levels of salinity. An estimated 2,000 hectares (of the 30,000 irrigated) has already been lost for normal crop production (Interview with Eng. Rui Brito UEM, Faculty of Agronomy and Forestry). | |||

Pollution by heavy metals is rarely measured or recorded. A recent GAS meeting indicated that after a relative extensive groundwater quality study led by UNICEF in the centre of Mozambique, only in some areas (around Gorongosa mountain) was mercury (Hg) found at levels above WHO standards (Minutes of meeting GAS, October 2009). | |||

==Groundwater use and management== | ==Groundwater use and management== | ||

=== Groundwater use=== | === Groundwater use=== | ||

| Line 344: | Line 386: | ||

Government of Mozambique (GOM). 1995. Política Nacional de Águas, Resolução do Conselho de Ministros nº 7/95 de 8 de Agosto, Boletim da República no. 34, 1ª Série de 23 de Agosto de 1995. | Government of Mozambique (GOM). 1995. Política Nacional de Águas, Resolução do Conselho de Ministros nº 7/95 de 8 de Agosto, Boletim da República no. 34, 1ª Série de 23 de Agosto de 1995. | ||

IWACO. | IWACO. 1985. Study of groundwater to supply Maputo. | ||

Worldbank. 2007. Mozambique Country Water Resources Assistance Strategy: Making Water Work for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction | Worldbank. 2007. Mozambique Country Water Resources Assistance Strategy: Making Water Work for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction | ||

Revision as of 16:17, 29 July 2015

Africa Groundwater Atlas >> Hydrogeology by country >> Hydrogeology of Mozambique

Authors

Lucas Chairuca, National Directorate of Water, Mozambique

Arjen Naafs, WaterAid, UK

Ivo van Haren, WE Consult, Mozambique

Kirsty Upton and Brighid Ó Dochartaigh, British Geological Survey, UK

Geographical Setting

General

The Zambezi River divides Mozambique into two topographical regions: to the north, a narrow coastal strip gives way to inland hills and low plateaus; and further west to highland areas including the Niassa, Namuli or Shire, Angonia and Tete highlands and the Makonde plateau. To the south of the Zambezi River, the lowlands cover a larger area inland from the coast, rising to the Mashonaland plateau and Lebombo Mountains located in the deep south.

| Estimated Population in 2013* | 25,833,752 |

| Rural Population (% of total) (2013)* | 68.3% |

| Total Surface Area* | 786,380 sq km |

| Agricultural Land (% of total area) (2012)* | 63.5% |

| Capital City | Maputo |

| Region | Eastern Africa |

| Border Countries | Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe |

| Annual Freshwater Withdrawal (2013)* | 884.2 Million cubic metres |

| Annual Freshwater Withdrawal for Agriculture (2013)* | 78.0% |

| Annual Freshwater Withdrawal for Domestic Use (2013)* | 19.2% |

| Annual Freshwater Withdrawal for Industry (2013)* | 2.8% |

| Rural Population with Access to Improved Water Source (2012)* | 35% |

| Urban Population with Access to Improved Water Source (2012)* | 80% |

* Source: World Bank

Climate

-

Koppen Geiger Climate Zones

-

Average Annual Precipitation

-

Average Temperature

Mozambique has a tropical climate, with a general wet season (October to March) and dry season (April to September). However, local climate varies significantly according to altitude. The highest rainfall is in coastal areas, decreasing to the north and south. Annual precipitation varies from 500 to 900 mm across the country.

Rainfall time-series and graphs of monthly average rainfall and temperature for each individual climate zone can be found on the Mozambique Climate Page.

For further detail on the climate datasets used see the climate resources section.

Surface water

|

The country is drained by five principal rivers and several smaller ones. The largest and most important is the Zambezi River. There are four significant lakes: Lake Niassa (or Malawi), Lake Chiuta, Lake Cahora Bassa and Lake Shirwa, all in the north.

|

|

Soil

|

Land cover

|

Geology

This section provides a summary of the geology of Mozambique. More detail can be found in the references listed at the bottom of this page. Many of these references can be accessed through the Africa Groundwater Literature Archive.

The geology map on this page shows a simplified version of the geology at a national scale (see the Geology resources page for more details). The map is available to download as a shapefile (.shp) for use in GIS packages.

A more detailed geological map at higher resolution was published in 2008 (see Geology: key references, below, for details).

| Key Formations | Period | Lithology | Structure |

| Unconsolidated sedimentary | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal sand dunes; Alluvium; Interior aeolian sand dunes; Lacustrine limestones; Marine reef and bioclastic sediments; Sand sheets with local gravel | Quaternary | Almost 70% of the area underlain by sedimentary basins in Mozambique has a cover of unconsolidated sediment. This is very commonly a 5 to 10 m thick weathered layer of clayey sand, sometimes overlain by valley (alluvial) sand, aeolian sand, and rare colluvial deposits. Particular deposits are:

Coastal beach and dune sands. Alluvium: alluvial sand, sandy soil, silt, gravel, lacustrine saline maud, pebble-bearing debris, estuarine and tidal flat sediment and back-barrier sediment. Interior dune and red aeolian sand, including the Topuito Formation. Lacustrine limestone. Marine reef, coral and bioclastic sediment. Sand sheets with local gravel. |

|

| Sedimentary - Cretaceous-Tertiary | |||

| Mazamba Formation; Jofane Formation; Inhaminga Formation; Mangulane Formation; Mapai Formation; Sena Formation; Lupata Group (Mazambulo Formation; Tchazica Formation) | Cretaceous (Tchazica Formation of Lupata Group is Jurassic) and Tertiary (Palaeogene-Neogene) | Mazamba Formation, Neogene - arkosic sandstones, in part conglomeratic

Jofane Formation, Neogene - sandstone and conglomeratic sandstone members, locally silicified. The Cabe Member comprises calcarenite, conglomerate and quartzite. Inhaminga Formation, Neogene - sandstone Mangulane Formation, Palaeogene - sandstone and limestone Sena Formation, Cretaceous - conglomerate and minor sandstone (including a thorium sandstone member), with a basal conglomerate member Lupata Group, Jurassic-Cretaceous: Monte Mazambulo Formation - conglomeratic sandstone; Tchazica Formation - sandstone and conglomerate.

The Southern or Mozambique Sedimentary Basin covers much of the southeast of Mozambique, and about 32% of the country as a whole, reaching a maximum width of 440km. The Northern or Rovuma Sedimentary Basin extends along a narrow outcrop from the Tanzanian border south to Ilha de Mozambique, and has a maximum onshore width of 120km. Both sedimentary basins were subject to several marine transgressions, the main one of which occurred in Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary. The sedimentary sequences are characterized by predominately continental series of arkosic sandstones in the western parts of the basins and mainly marine and transitional series in the coastal parts. |

Post-Karoo sedimentation was largely controlled by the development of the East African Rift System and related tectonic events. The Tertiary saw subsidence along deep N-S oriented troughs along the axis of the Mozambique Channel, in which sedimentation occurred. The sedimentary rocks are sometimes intensely faulted, but only slightly folded, with slightly developed arched structures. The best developed rift valleys are the Chire-Urema and the Funhalouro-Mabote grabens (the latter is part of the larger Mazunga Graben). |

| Sedimentary - Mesozoic-Palaeozoic | |||

| Upper Karoo Group (Lualadzi Formation, Zumbo Formation), Magoe Formation | Jurassic to Cretaceous | Magoe Formation, Cretaceous - limestone and sandstone

Zumbo Formation, Upper Karoo Group, Triassic - sandstone and silicified sandstone Lualadzi Formation, Upper Karoo Group, Jurassic - red sandstone, locally silicified The lower sequence of Karoo sedimentary rocks contains mainly very fine grained (largely mudstones), and sometimes contain carbonaceous beds. The upper sequence is more sandy. |

Post-Cambrian crustal development was characterised by the break up of the supercontinent Gondwana. From Permian to Jurassic, rifts developed along the E-W trending Limpopo and Zambeze Belts, where deep troughs were filled with continental Karoo sediments, forming the Middle Zambeze Basin. In the north of Mozambique, the Maniamba Basin and smaller outcrops of Karoo sedimentary rocks form part of a larger Karoo basin in Tanzania. |

| Igneous | |||

| Karoo volcanic rocks and Post-Karoo largely intrusive igneous rocks, including the volcanic Movene Formation, Umbeluzi Formation (including Basalt Member), Rio Nhavudezi Formation, Bangomatete Formation, Rio Mazoe Formation; and intrusive igneous Gorongosa Suite and Rukore Suite | Jurassic to Early Cretaceous | The Karoo terminated with a period of intensive volcanic activity, dominated by basaltic and rhyolitic outflows, with the resulting rocks including basalt, rhyolite, andesite, tuff, ignimbrite and volcanic breccia. The volcanic sequence consists of a number of superposed lava flows, emerging from tension faults and fissures along the margins of the Basement Complex and along the widening Zambeze and Limpopo Basins. A line of outcrops is found along these margins, of which the Libombo Range in the southwest is the most important. The outcrops continue in a narrow strip to the north of the Zambeze. The basalt along the coast of Nampula province is considered to form part of the same system.

After Karoo volcanism, local igneous activities continued along borders of the East African Rift System and the Zimbabwe and Kaapvaal Cratons. The Post-Karoo igneous phenomena are dispersed and produced rocks with a wide variety of composition, genesis and age, including granite, syenite, gabbro, feldspar porphyry and mafic dykes. The late Jurassic to early Cretaceous batholith of the Serra da Gorongosa, consisting of gabbroic and granitic rocks, and the Middle Cretaceous alkaline lavas of the Lupata region are the most important features. More dispersed examples are the Cretaceous syenitic plutons of Milange, Chiperone and Derre and the carbonatite complexes and Upper Tertiary vents of basic to ultra-basic composition in the Sena region. |

|

| Precambrian Basement Complex | |||

| Archaean to Proterozoic | Many named groups and formations | The Precambrian Basement Complex occupies Manica, the western part of Sofala and almost the entire region north of the Zambeze. The formations of the northern part of Mozambique (a large part of the provinces of Zambezi, Nampula, Cabo Delgado and Niassa and the northern part of the province of Tete), comprise of high-grade metamorphic rock, forming part of the Mozambique Metamorphic Belt. This belt is dominated by gneiss and a gneiss-granite-migmatite complex with local meta sediments, charnockite series and a gabbro-anorthosite complex in the center of Tete province. In the Manica region (the Mozambican Province in the centre of the country, bordering Zimbabwe) one finds remnants of the Early Precambrian Zimbabwe Craton, dominated by greenschists.

The Basement Complex includes many metamorphic and meta-igneous rock types, including granite, granofels, granodiorite, gneiss (including leucocratic gneiss, quartz-feldspar gneiss, orthogneiss, paragneiss, migmatitic paragneiss, granitic gneiss, calc-silicate gneiss, biotite-gneiss, mica gneiss, augen gneiss, magmatic gneiss and garnet gneiss), quartz diorite, tonalite, , gabbro, pyroxene diorite, garnet-sillimanite, metasiliciclastic sedimentary rocks, metagranite, hornblende gneiss, amphibolite, amygdaloidal andesitic lava, orthoquartzite, quartzite, arkosic quartzite, mafic metavolvanics including meta-tuff, siltstone, claystone, marble, meta-sandstone, muscovite-biotite schist, mica schist, arenaceous mica schist, migmatite, mylonite. |

|

Hydrogeology

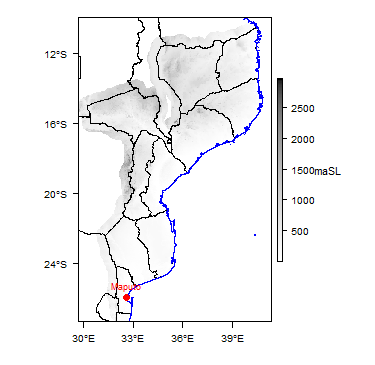

This section provides a summary of the hydrogeology of the main aquifers in Mozambique. More information is available in the references listed at the bottom of this page. Many of these references can be accessed through the Africa Groundwater Literature Archive.

The hydrogeology map on this page shows a simplified version of the type and productivity of the main aquifers at a national scale (see the Aquifer properties resource page for more details). The map is available to download as a shapefile (.shp) for use in GIS packages.

A more detailed hydrogeological map was published by DNA (1987).

File:Mozambique Hydrogeology.png

Summary

Mozambique can be divided into three major hydrogeological provinces (DNA 1987). These are:

1. Basement Complex 2. Volcanic (and other igneous) terrains 3. Sedimentary Basins.

The most significant sedimentary basin is the Mozambique Sedimentary Basin to the south of the Save River, in southern Mozambique. Other, smaller, sedimentary basins include the Mozambique Sedimentary basin to the north of the Save River; the Northern/Rovuma Sedimentary Basin which has a narrow linear outcrop in the northeast of the country; the Middle Zambeze Sedimentary Basin, in the centre-west of the country; and the Maniamba Sedimentary Basin, which has a very small outcrop in the northwest of the country.

Unconsolidated

| Named Aquifers | General Description | Water quantity issues | Water quality issues | Recharge |

| Unconsolidated aquifers cover a large part of the Mozambique basin, especially south of the Save River; and occur in river valleys and in some dune and coastal areas across the country.

Key aquifers include sand layers within clayey alluvium; loamy silty to medium grained aeolian and beach/marine sands; and areas of weathered fine grained clayey sands overlying consolidated rocks. Less frequent, but highly productive, are thick sandy and gravelly alluvium in valleys. A belt of dune sands is developed along the entire coast of southern Mozambique, south of the Save River. These porous aeolian sands form a regional unconfined aquifer which can be very productive, as shown by boreholes in the Ponta de Ouro and Tofo aquifers, and can contain fresh groundwater. Permeability decreases from the coast inland, as a consequence of increased clay content. These unconsolidated sands are frequently underlain by more productive deeper consolidated aquifers, and there can be hydraulic continuity between the upper unconsolidated and deeper consolidated aquifer. For example, dune sands along the Inhambane coast overlie very productive limestones of the Jofane Formation, except in the area around Inharrime, where the dunes cover the low productive argillaceous sandstones of the Inharrime Formation. Significant thicknesses of alluvium have been developed along the main river valleys, and may form productive, stratified aquifers with good water quality. The aquifer layers can be confined or unconfined, depending on local circumstances. The central reaches of the Limpopo and Incomati have especially high-yielding prospects, with specific yields of up to 20 m³/h/m.

|

In most areas of the southern dune belt, the nearness of the aquifer to the sea, and sometimes to lagoonal inland depressions, means that the aquifer often contains brackish to saline water, which limits its use. However, there is fresh groundwater between Homoine and Massinga.

In alluvial aquifers along the main river valleys, groundwater is generally of good quality. However, in the lower reaches of the main main valleys increased groundwater mineralization is often seen, as a consequence of occasional marine inundations or longer term sea-water intrusions near the river mouth. In the centre of the Incomati valley, the good prospects are offset by the existence of highly mineralized groundwater. |

Sedimentary - Intergranular Flow

| Named Aquifers | General Description | Water quantity issues | Water quality issues | Recharge |

Sedimentary - Intergranular & Fracture Flow

| Named Aquifers | General Description | Water quantity issues | Water quality issues | Recharge |

Sedimentary - Fracture Flow

| Named Aquifers | General Description | Water quantity issues | Water quality issues | Recharge |

Basement

| Named Aquifers | General Description | Water quantity issues | Water quality issues | Recharge |

Groundwater Status

Recharge

Reliable information on natural aquifer recharge in Mozambique is very scarce. Only a few studies have been conducted, in a few small areas. Recharge to sandy soils around Maputo was studied by IWACO in 1985 and was found to be somewhere between 140 and 185 mm per year, which is around 20% of the total precipitation. In other areas with sandy soils and higher precipitation, recharge was found to be higher, for example, 210 and 350 mm per year, or around 30% of annual rainfall, near Pemba. In drier areas with less permeable soils, such as the semi-arid Chitima region near Tete, recharge values of less than 10 mm per year were estimated (IWACO 1985, DNA 1987).

Groundwater quantity

There are many potential problems linked to the use of groundwater in Mozambique. Little information exists on the present status of groundwater quantity, and there is no quantitative information on groundwater use and recharge. Before groundwater can be used on a large scale for irrigation or other uses, extensive research is needed (DNA 1987; British Geological Survey 2002).

Groundwater has a significant role to play in the supply of drinking water, but is currently only used sparsely for irrigation due to the following factors:

• Mozambique still has enough areas that can be developed for irrigation using surface water resources. • There is limited to no information on the potential of aquifers and yields of individual boreholes. • Large areas in southern Mozambique are deemed unsuitable for groundwater abstraction due to salinity issues. The exact extent of these areas is undetermined.

It seems that the lack of information (which means there is an unknown risk of drilling low yielding boreholes and/or incurring high drilling costs) is a larger constraining factor than the actual potential of the groundwater. As well as this, there is a general consensus that surface water is more cost-effective for irrigation than groundwater. The potential for, in particular, large surface water irrigation schemes is still present in Mozambique, and thus the interest for groundwater is low. Furthermore, the following can be concluded: 1) There is little knowledge of groundwater use around non-perennial rivers 2) Groundwater for irrigation is mainly used for subsistence farming, except for certain labour intensive areas around Maputo. 3) Legislation of groundwater abstraction is in its infancy in Mozambique. Capacity is very limited presently. Technical assistance and capacity training in this area is essential. 4) Groundwater is probably underutilised at present, as potential users do not have knowledge of or access to the groundwater potential in their area.

Groundwater quality

Little information is available on the quality of groundwater in the aquifers of Mozambique. The available information suggests that the groundwater is for the larger part fresh and of acceptable quality, though often of limited quantity, especially in the aquifers of the Basement Complex and the Volcanic Terrains.

Significant salinity problems are experienced in some parts of the Tertiary aquifers in the south, as a result of natural seawater intrusion, forming areas with brackish groundwater. In large parts of Gaza, Maputo and Inhambane Province, groundwater in the main aquifer (from 20 – 80 m depth) has Electrical Conductivity values well above the WHO drinking water standards of 2000 µS/cm. These values also make the groundwater unsuitable for many crops and for livestock watering. In some particular instances (e.g. at Chokwe and Chibugo), extra deep boreholes (100-150 m) have been drilled to reach fresh water in aquifers. Such boreholes are, however, too expensive to consider for irrigation (particularly as proper sealing of the upper saline aquifer needs to be achieved).

There is risk of pollution in the vicinity of industrial and urban developments, including from sewage effluent, from centres of petroleum and chemical manufacture, and from ports, as well as from agricultural activity. Pollution incidence is likely to be greatest in the coastal lowlands (DNA 1987, British Geological Survey 2002).

Localized groundwater pollution is known to be occurring in the Chokwe (Gaza Province) area, where extensive irrigation has taken place (using surface water) since the 1930s. This has raised the local groundwater table and has led to increased levels of salinity. An estimated 2,000 hectares (of the 30,000 irrigated) has already been lost for normal crop production (Interview with Eng. Rui Brito UEM, Faculty of Agronomy and Forestry).

Pollution by heavy metals is rarely measured or recorded. A recent GAS meeting indicated that after a relative extensive groundwater quality study led by UNICEF in the centre of Mozambique, only in some areas (around Gorongosa mountain) was mercury (Hg) found at levels above WHO standards (Minutes of meeting GAS, October 2009).

Groundwater use and management

Groundwater use

Groundwater management

Groundwater monitoring

Transboundary aquifers

For further information about transboundary aquifers, please see the Transboundary aquifers resources page

References

The following references provide more information on the geology and hydrogeology of Mozambique. These, and others, can be accessed through the Africa Groundwater Literature Archive.

Geology: key references

A revised national geological map was published in 2008, as part of the Mineral Resources Management Capacity Building Project:

Republica de Mocambique - Ministerio dos Recursos Minerais – Direccao Nacional De Geologia. 2008. Carta Geologica Escala 1:1,000,000.

The Map Explanation has 4 volumes:

GTK Consortium. 2006. Carta Geologica Escala 1:1,000,000: Map Explanation, Volume 1. Describes the area south of the Save River

GTK Consortium. 2006. Carta Geologica Escala 1:1,000,000: Map Explanation, Volume 2. Describes the central part of Mozambique.

GTK Consortium. 2006. Carta Geologica Escala 1:1,000,000: Map Explanation, Volume 3. Describes the eastern-central part of Mozambique (Zambezi Province).

GTK Consortium. 2006. Carta Geologica Escala 1:1,000,000: Map Explanation, Volume 4. Describes the western-central part of Mozambique (Tete Province). Report_B6_f1_screen

Hydrogeology: key references

The main source of hydrogeological information for Mozambique is:

Ferro and Bouman / DNA. 1987. Explanatory Notes to the Hydrogeological Map of Mozambique: 1:1,000,000.

This map is largely based on the 1978 national geological map (Afonso 1987), and limited hydrogeological field data. The national geological map was updated in 2008 (see Geology: key references, above), but the 1987 national hydrogeological map has not yet been updated.

Other hydrogeological references are:

African Development Bank. 2002. Mozambique Water and Sanitation Sector Review. Prepared by SEED, May 2002.

African Development Bank. 2005. Rapid Assessment of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation. Mozambique Requirements for Meeting the MDGs, March 2005

British Geological Survey (BGS). 2002. Groundwater Quality: Mozambique.

DNA. 1999. Water resources of Mozambique.

Government of Mozambique (GOM). 1995. Política Nacional de Águas, Resolução do Conselho de Ministros nº 7/95 de 8 de Agosto, Boletim da República no. 34, 1ª Série de 23 de Agosto de 1995.

IWACO. 1985. Study of groundwater to supply Maputo.

Worldbank. 2007. Mozambique Country Water Resources Assistance Strategy: Making Water Work for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction

The DNA (National Water Department), together with donors, particularly UNICEF, have carried out several drilling programs. Drilling reports from these programmes provide lithological information (typically simple but relatively accurate descriptions); borehole information (depth, location filters etc); and hydrogeological information (water levels, main water strikes, some water quality parameters). Proper pumping tests data are rare: most constant discharge tests were less than 1 hour, and in most cases only air-lift tests were done. This information from drilling programmes is not available in one report or single database: the DPOPH (Provincial Departments of Public Works and Housing) have databases with hydrogeological data per province.

Particular drilling programmes were:

ASNANI. 2004-2008. Executed by DNA and financed by ADB. Hundreds of boreholes drilled in Nampula and Niassa Provinces.

MCA (Millenium Challenge Account. 2008-2012. Hundreds of boreholes drilled in Nampula and Cabo Delgado Provinces.

UNICEF One Million Initiative. 2008-2012. Hundreds of boreholes drilled in the Tete, Manica and Sofala Provinces.

Return to the index pages

Africa Groundwater Atlas >> Hydrogeology by country >> Hydrogeology of Mozambique